System Calls

System calls, commonly just called syscalls, are the way that a user space process interfaces with the kernel. It’s a way for unprivileged instructions to have the kernel execute privileged instructions on its behalf, such as access to an operating system service or a hardware-related service.

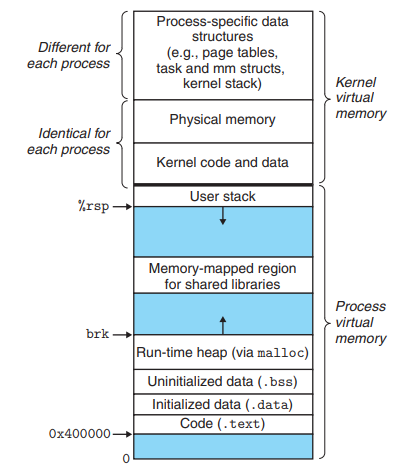

The Linux security model supports different levels of privileges and enforces them through hardware (see the status register). Because of its lower privilege, user space processes cannot access hardware directly, manipulate other user processes or the kernel and is limited to and constrained by its virtual memory space, which is only a portion of the total physical memory on the system. Any memory accesses are mapped from virtual memory to physical memory and controlled by the memory management unit.

The system call names are portable, in the sense that the names don’t change across distributions (this is for Linux, obviously), so a library for a particular architecture increases portability. However, the names, number of parameters and their order is architecture dependent. More on this later in the section on Library Wrapper Functions.

Making the Call

A userland process will make a syscall when it needs access to the system’s hardware, such as accessing protected memory, creating/forking child processes, creating a file, any kind of I/O, et al. Applications running in user space request these services by making system calls, which, depending on the chipset, use different techniques to transfer control to the kernel (a privilege mode switch).

Older RISC processors only are able to initiate this by a software interrupt (generically referred to as a trap), but more recent CISC architectures can avoid the overhead of a software interrupt by enabling a fast entry to the kernel using the SYSENTER and SYSEXIT instructions.

SYSCALL/SYSRETwere created by AMD andSYSENTER/SYSEXITby Intel, but they do the same thing.

Either technique enables the necessary privilege switch switch from to kernel mode. Control passes to the kernel, and the CPU will run the privileged instructions only if the requesting program has permissions to access the requested service (whether the operation is legal or illegal is out of scope of this brief introduction to system calls).

If legal, the kernel executes the instructions, switches the privilege mode back to the unprivileged user mode and returns control to the calling process.

Importantly, most Unix derivatives, like Linux, don’t perform a process context switch when processing a syscall. Instead, they do a privilege context switch, and the system call is processed in the context of the process that called it.

Privilege Context Switch

At this point, a legitimate question would be: What is the difference between a process context switch and a privilege context switch?

A process context switch can be expensive. The following context information for the process needs to be saved to the process control block (PCB) data structure for every context switch, when the old process context is saved and the new one loaded from the PCB:

- The current process' command pointer (aka instruction pointer (IP) in Intel

x86microprocessors). - The content of the general-purpose CPU registers.

- Stack and frame pointers.

- The CPU process status word.

- et al.

The kernel, now running in kernel mode, performs the operations and returns. If there is an error, it sets the error code in the global

errnovariable and instructs the wrapper function to return a non-zero return code, usually -1, so the user space process knows there was an error.It also restores the previous process context from the PCB before returning. The value of the status register is also updated to reflect that there has been another privilege context switch, that is, from kernel space back to user space.

In addition, when performing a process context switch, if the processor memory caches are flushed, then every subsequent memory lookup will result in a cache miss that will need to be fetched from physical memory through the MMU.

So, saving and restoring processor state, memory cache misses and operations that occur or can be a consequence of a process context switch contributes to why these context switches are referred to as expensive.

A privilege context switch, on the other hand, is processed within the same context as the process that invoked the system call. As the name states, the switch that occurs is a change of privilege, not of the process, from user mode to kernel mode. The MMU has set the kernel mappings as non-executable, so they cannot be accessed while in user mode. The syscall has a trap that triggers a jump to a location in the kernel called the interrupt vector table that contains mappings to procedures that will be executed and then carry out the instructions on behalf of the user process.

Kernel memory is mapped into the process' virtual memory at the conceptual top of the virtual memory space (the highest memory addresses).

Note, however, that the virtual kernel space may be isolated from the process virtual memory space, a kernel feature known as kernel page-table isolation. This was done to mitigate the Meltdown security vulnerability.

Library Wrapper Functions

There is usually a thin library wrapper around the syscall itself that has the same name as that of the syscall. This wrapper function then calls through to the system call API interface, usually an implementation of the libc library like glibc.

How do the library wrapper functions know the number of parameters to pass and their order? This is specific to the architecture, so one must consult the particular architecture’s application binary interface (ABI) and its particular calling convention for answers (for instance, the x86 calling convention).

The function arguments will be the unique system call number and the values for the processor registers. Let’s look at an example of some Go library code that isn’t interfaces with the glibc. The developer wouldn’t call these functions directly, rather the API would define functions that usually have the same name as the implied syscall that would be used in any application code (like read, write, open, etc.).

func RawSyscall6(trap, a1, a2, a3, a4, a5, a6 uintptr) (r1, r2 uintptr, err Errno)

func RawSyscall(trap, a1, a2, a3 uintptr) (r1, r2 uintptr, err Errno) {

return RawSyscall6(trap, a1, a2, a3, 0, 0, 0)

}

func Syscall(trap, a1, a2, a3 uintptr) (r1, r2 uintptr, err Errno) {

runtime_entersyscall()

// RawSyscall6 is fine because it is implemented in assembly and thus

// has no coverage instrumentation.

r1, r2, err = RawSyscall6(trap, a1, a2, a3, 0, 0, 0)

runtime_exitsyscall()

return

}

func Syscall6(trap, a1, a2, a3, a4, a5, a6 uintptr) (r1, r2 uintptr, err Errno) {

runtime_entersyscall()

r1, r2, err = RawSyscall6(trap, a1, a2, a3, a4, a5, a6)

runtime_exitsyscall()

return

}

( The assembly for amd64 can be viewed in the Go repository. )

Incidentally, the kernel knows which subroutine to execute to run when trapped by looking up the software interrupt integer parameter of the syscall and then using this integer to look up the function in the interrupt vector table.

When a trap occurs, the trap (software interrupt) instruction forces the program to jump to a well-known address based on the number of the interrupt, which is provided as a parameter. In the example above, the interrupt number is passed as the

trapfunction parameter.

A high-level language such as C, Go, Python, etc., will call these lower-level wrapper functions from its own API, and, as a result, most developers make syscalls without even knowing it.

See the Examples section to see these higher-level API functions.

Emulation

I wrote a recent article On Virtual Machines that has a section on emulating syscalls in a virtualized environment. Please see that post for more information.

strace

strace is a well-known tool used to trace the system calls and signals of a process. It takes the command it’s tracing as an argument:

$ strace ls

Let’s take a look at using it to trace a very simple C program:

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

puts("Hello, world!");

}

Compile it and run:

$ gcc -o hello hello.c

$ strace -c ./hello

Hello, world!

% time seconds usecs/call calls errors syscall

------ ----------- ----------- --------- --------- ----------------

0.00 0.000000 0 1 read

0.00 0.000000 0 1 write

0.00 0.000000 0 2 close

0.00 0.000000 0 3 fstat

0.00 0.000000 0 7 mmap

0.00 0.000000 0 3 mprotect

0.00 0.000000 0 1 munmap

0.00 0.000000 0 3 brk

0.00 0.000000 0 6 pread64

0.00 0.000000 0 1 1 access

0.00 0.000000 0 1 execve

0.00 0.000000 0 2 1 arch_prctl

0.00 0.000000 0 2 openat

------ ----------- ----------- --------- --------- ----------------

100.00 0.000000 33 2 total

From the

straceman page:-c --summary-only Count time, calls, and errors for each system call and report a summary on program exit, suppressing the regular output. This attempts to show system time (CPU time spent running in the kernel) independent of wall clock time. If -c is used with -f, only aggregate totals for all traced processes are kept.Omit the

-coption to get see the about the calls parameters.

This is a great way to get an idea of not only the system calls made by a process but their parameters that give a glimpse into how user space communicates with kernel space.

For more insights, see Liz Rice’s illuminating talk on The Beginner’s Guide to Linux Syscalls in which she recreates strace in a small amount of Go code.

There are other tools like

ftracethat are worth researching.

Misc

Although I won’t enumerate them here, there are six categories of system calls:

- Process control

- File management

- Device management

- Information maintenance

- Communication

- Protection

The number of system calls varies according to the operating system. For instance, Linux has over 300 (see the syscalls(2) man page for a complete list), FreeBSD has over 500 and Windows has over 2000.

Examples

Let’s disassemble this tiny C program:

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

puts("Hello, world!");

}

$ gcc -c hello.c

$ objdump -d hello.o

hello.o: file format elf64-x86-64

Disassembly of section .text:

0000000000000000 <main>:

0: f3 0f 1e fa endbr64

4: 55 push %rbp

5: 48 89 e5 mov %rsp,%rbp

8: 48 8d 3d 00 00 00 00 lea 0x0(%rip),%rdi # f <main+0xf>

f: e8 00 00 00 00 callq 14 <main+0x14>

14: b8 00 00 00 00 mov $0x0,%eax

19: 5d pop %rbp

1a: c3 retq

The subroutine call callq is probably the system call, but to see it more explicitly, let’s use our old friend gdb. Here, we’ll target just the function calls we’re interested in:

$ gdb -batch -ex 'file hello' -ex 'disassemble main' -ex 'disassemble puts'

Dump of assembler code for function main:

0x0000000000001149 <+0>: endbr64

0x000000000000114d <+4>: push rbp

0x000000000000114e <+5>: mov rbp,rsp

0x0000000000001151 <+8>: lea rdi,[rip+0xeac] # 0x2004

0x0000000000001158 <+15>: call 0x1050 <puts@plt>

0x000000000000115d <+20>: mov eax,0x0

0x0000000000001162 <+25>: pop rbp

0x0000000000001163 <+26>: ret

End of assembler dump.

Dump of assembler code for function puts@plt:

0x0000000000001050 <+0>: endbr64

0x0000000000001054 <+4>: bnd jmp QWORD PTR [rip+0x2f75] # 0x3fd0 <puts@got.plt>

0x000000000000105b <+11>: nop DWORD PTR [rax+rax*1+0x0]

End of assembler dump.

Now, we can see it call into the glibc wrapper function puts (memory address 0x1050) and then the jump to the privileged kernel instructions, which is allowable now that the context has switched to kernel mode.

We can compile the program and use

objdump -dto get the full disassembly.

The following are only examples of how a high-level language like C and Go have their own library functions that a developer would use in their application code. They are obviously easier to use than writing assembly or even calling the low-level library wrapper functions themselves, such as the glibc implementation

#define _GNU_SOURCE

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/syscall.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <signal.h>

int

main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

pid_t tid;

tid = syscall(SYS_gettid);

syscall(SYS_tgkill, getpid(), tid, SIGHUP);

}

import (

"fmt"

"os"

"syscall"

)

func main() {

_, errno := syscall.Write(1, []byte("Hello, world!"))

if errno != nil {

fmt.Printf("Failed to write: %v", errno)

os.Exit(1)

}

}

Summary

In this article, I tried to strike a balance between going deeper than most introductory articles on system calls without getting too much in the weeds. This was difficult to do, and I may end up doing a follow-up to this or expanding these sections in the future, as many of these subjects are very important and interesting and, as such, owed more than just a superficial coating.