I remember the first time I heard of virtual machines and hypervisors. It was way back in the naughties around 2003 or 2004, and I remember thinking something along the lines of: “What kind of magic is this?”

At that time and even now, I feel that virtual machines and virtualization in general are technologies that people use all the time without having to know the slightest thing about what it is and how it’s done. In fact, many times we don’t even know that we’re operating in a virtualized environment.

And I think that’s peachy. There’s nothing wrong with that. It’s impossible to know everything about every layer of technology. It’s easy to build a mental model around what a virtual machine is and the benefits it provides, and that’s usually enough.

However, once you start doing anything serious with containers and OS-level virtualization that all changes. At least, that has been my experience.

Why? In a containerized world, it’s extremely helpful, necessary even, to know what the differences are and the security implications of running a process in a container versus a virtual machine. (There are other reasons to want to dig into how virtual machines work, of course, but this was the impetus for me.)

That’s a big subject, and in order to be able to speak cogently and confidently about it, you have to know a fair bit about the Linux kernel.

There are a lot of similarities between these concepts, and many of them overlap. I’m going to briefly (superficially) define these terms so that we have proper working definitions in order to construct the necessary mental model for the how a virtual machine works.

Glossary

CPU Modes

CPU modes, also called processor modes, are CPU operating modes, and, as part of the security model of the system, they place restrictions on processes and determine the type and scope of allowable operations. For instance, it allows the kernel to run at a higher privilege level than any user application. Conversely, user mode cannot access any memory other than a limited view (its virtual memory), and it does not have access to system resources (to access those resources, it needs to have the kernel act on its behalf).

The most common two modes are kernel mode and user mode. User mode requests the kernel to perform privileged operations on its behalf via system calls.

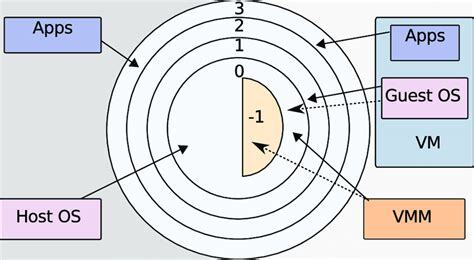

There is also a third mode that is effectuated when running one or more virtual machines managed by a virtual machine monitor (

VMM) or hypervisor. For instance, when a hypervisor is present, a processor that supports hardware-assisted virtualization can run at ring level -1 (more privileged than level 0) and the guest kernel(s) run at 0. This allows theVMMto run one or many guest operating systems beneath it (more on that later).

Kernel mode is also referred to as privileged mode or supervisor mode and user mode as restricted mode, et al.

In kernel mode, the processor can execute anything that is allowed by its architecture, which in effect allows any instruction. On the other hand, user mode is going to be a restricted subset of those operations.

Moving from one mode to another necessitates a privilege [context switch]. Ring-based security is closely related to the idea of processor modes.

Privilege Rings

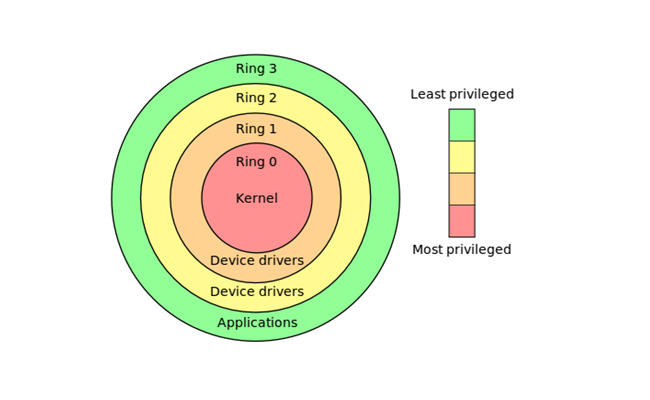

Privilege rings, also known as protection rings, are concentric circles of privilege from 0 (most privileged) to 3 (least privileged). Ring 0, for example, allows for direct access of the hardware on the machine. This is the level in which the kernel and device drivers run. Ring 3 is for user mode applications.

A process running in kernel mode is operating at ring 0, and a user mode process is operating at ring 3.

Interestingly, modern x86 CPUs support hardware-assisted virtualization, which allows the hypervisor to run in an extra-privileged below ring 0, essentially making it ring -1. When this occurs, the guest kernels run at ring 0, with the end result being that there doesn’t need to be any hacky workarounds to enable full virtualization. More on this later.

The privilege rings are hardware enforced by a CPU status register.

User Space and Kernel Space

Conceptually, user space and kernel space is a way for an operation system to segregate virtual memory. Kernel space refers to the execution of privileged instructions, like the kernel itself, device drivers, eBPF programs, etc., and the user space (or userland) is where user application programs are executed like web browsers, shells, editors, libc, etc.

Importantly, the separation of kernel space from user space allows for memory protection.

How does user space interface with kernel space? Through the system call API.

System Calls

User space processes programmatically request services on behalf of the kernel through system calls (syscalls). These are requests for file management, process control, communication, et al.

For most operating systems, syscalls are only made from user space processes.

The userland process, restricted to its own virtual address space, cannot access or modify other processes or the kernel itself. In addition, anything running in user mode is prevented from directly accessing the machine hardware and must rely on this system call interface to ask the kernel to perform the task.

A lot of things happen that is outside the scope of this brief definition, but the end result is a mode switch from restricted (user) to unrestricted (kernel) mode. Control is passed to the kernel which, running at the highest privilege (ring 0), checks to ensure that the process is allowed to make the syscall, and then directly accesses the hardware and performs the operation on behalf of the userland process. Control is then returned to the calling program.

As noted, system calls necessitate a mode context switch, but it is not a process context switch. Instead, it’s a privilege context switch. The appropriate bits are set in the processor status register, and the mode is changed from user mode to kernel mode.

Most programming languages have libraries that hide the details of system calls from the developer. For instance, a higher-level programming language like Python or Go would have APIs that wrap the actual lower-level call through to the underlying C library.

For example, a common way in Go to open a file on the filesystem is with the os.Open library call. If you were to follow this down the rabbit hole, you will eventually come to the RawSyscall6 stub, where, according to the comment above it, declares that this function is linked to particular OS file in runtime/internal/syscall and finally the Assembly for the particular machine architecture (in my case, amd64). This calls the libc (or possibly glibc) syscall interface API.

Examples of common syscalls are

open,read,write,close,wait,exec,fork,exit, andkill. View the man page for more information about each one:$ man 2 open

In my opinion, the key thing to understand about how system calls work is that it generates a software interrupt, or trap, that initiates the privilege context switch. The trap tells the processor to jump to a well-known address based on the trap’s parameter, which is an interrupt number. This number is a lookup into the interrupt vector table, which is a data structure that maps these well-known interrupt numbers with a location in memory to a callback that will handle the trap.

Making a system call uses the trap mechanism to (mode) switch to a well-defined point in the kernel, which then runs all the instructions in kernel mode.

Now, at long last, we can move on to the point of this fantastic article.

Virtual Machines

Virtual machines have been around a long time. IBM built research mainframes in the 1960’s that allowed for full virtualization, and once Intel and AMD introduced the hardware extensions into their chips in 2005 and 2006, respectively, that they really took off as a prolific tool in every developer’s toolbox.

For early examples of computers capable of running virtual machine the IBM CP-40 and the IBM SIMMON hypervisor.

In order to run, virtual machines need to have a piece of hardware or software installed to manage them. Let’s take a look at a software example.

Virtual Machine Monitors

To run a virtual machine, there needs to be a virtual machine monitor (VMM) (perhaps better known as a hypervisor), installed that manages the guest operating systems. It will partition the hardware resources to each virtual machine.

The guest machines all have virtual access to the host machine’s hardware provided by the VMM, and most of their instructions (i.e., unprivileged instructions) are run directly by the real processor (as opposed to full emulation). We’ll soon take a look at how the guest machines, running at a ring level higher than 0, are able to have its privileged instructions emulated by the VMM.

The machine on which the hypervisor runs is called the host machine, and all of the virtual machines are the guest machines.

The term hypervisor was coined in 1970 and means the supervisor of the supervisors (the term supervisor refers to a kernel).

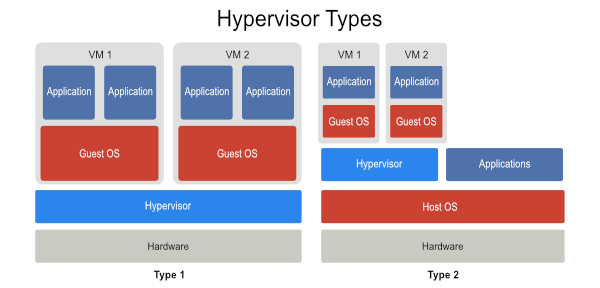

There are two types:

-

Type 1

Runs on bare metal, that is it runs directly on top of the hardware, and the guest operating systems it monitors are above it, conceptually. It directly controls the hardware.

-

Type 2

Runs in user space as a process on top of the host (or native) operating system, and its guest operating systems are above it, conceptually. The host machine has direct control of the hardware.

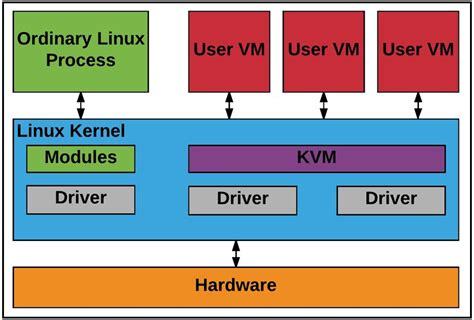

Of course, there is a type that doesn’t fit neatly into either of these conceptual models, and that is KVM (Kernel-based Virtual Machine). KVM is a Linux kernel module that effectively turns the host operating system into a hypervisor, which is why it’s usually included when talking about Type 1 VMMs.

Ok, so far, so good. But since the virtual machine isn’t a real machine and only has proxied access to the real hardware, how can it possibly run privileged instructions in kernel mode? In other words, if the entire virtual machine, which includes its kernel, runs in a privilege ring higher than ring 0 (kernel/privileged mode), how can it possibly have a way to have its privileged instructions executed?

Let’s look at one answer weeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeee

Trap-and-Emulate

The implementation style of trap-and-emulate became the prevalent method, although there were others. Some researchers have referred to this as the classical style of virtualization.

The fundamental idea behind trap-and-emulate is that the VMM will allow as many non-privileged system calls from the guest OS through as possible (that is, it allows the guest OS to perform these actions directly without intervention from the VMM), and only to emulate the ones that are privileged and legal. If illegal, the hypervisor will terminate the operation. The emulation that the VMM performs is the behavior that the guest OS expects from the hardware.

However, there were problems. The dominant x86 processor platforms, Intel and AMD, didn’t support the trapping of privileged instructions. So, nothing would happen if a processor was running in user mode and attempted to execute a privileged instruction.

This was a huge obstacle and made full virtualization on these platforms impossible. After all, if a privileged instruction is ignored, the trap never happens, and the VMM would have no way of knowing about it. The end result was there was no emulation and full virtualization was out-of-reach, at least for this platforms.

There were two prevalent hacks to work around this issue. Let’s take a look at them now.

x86 Workarounds

Binary Translation

With binary translation, the VMM pre-scans the input instruction stream for privileged instructions (i.e., instructions that are to only be run in kernel mode) and replaces them with traps that the VMM can intercept.

Of course, the non-privileged instructions are executed by the processor as usual.

Paravirtualization

Paravirtualization will modify the guest kernel and replace any privileged instructions with API calls to the VMM. These act like a system call, which triggers a trap and a privilege context switch to the VMM.

Although it is higher performing than binary translation, since it requires access to and modifying of the kernel, it doesn’t work in closed-source operating systems like Windows.

Hardware-assisted Virtualization

With the advent of hardware-assisted virtualization in Intel and AMD CPUs, binary translation and paravirtualization were obsoleted. As we saw in the graphic in the privilege rings section, the hardware now supports an extra-privileged virtualized mode called vmx root mode that runs the hypervisor in ring -1 and the guest machine in ring 0 (so, the guests think they are running as the host OS).

This means there is no need to either replace any instructions or intrusively modify the kernel; the guest operating system remains unmodified.

Summary

That’s it for now. I intend to write more posts about virtualization, and I also intend to revisit this post and update and augment when necessary.

Hopefully, these brief overview has gone a bit more in-depth than most introduction tutorials on the subject of virtual machines. For me, I wasn’t able to begin to wrap my head around the subject until I understood a bit more about memory protection and processor modes.