GDB is a wonderful tool and a great way to learn about virtual memory and how it’s laid out in a running program.

I’ve recently read this sweet book which explores GDB in some depth, so let’s look at some of its useful commands. Of course, this is not exhaustive.

I’ve already written several articles where I’ve used GDB:

Contents

- Breakpoints

- Breakpoint Command Lists

- Watchpoints

- Other GDB Commands

- Miscellaneous

- Text User Interface Mode

Breakpoints

Set Persistent Breakpoint

- b(reak) function

- b(reak) line_number

- b(reak) filename:function

- b(reak) filename:line_number

Set Temporary Breakpoint

- tb(reak) function

- tb(reak) line_number

- tb(reak) filename:function

- tb(reak) filename:line_number

Conditional Breakpoint

-

At definition.

-

b(reak) break-args if (condition)

break main if argc > 1break 8 if slen(argv[1]) == 6b main if string==NULL && i < 0

Note that as long as the binary has been compiled with the symbol table that you can reference variables and functions names.

-

-

By reference. This will turn normal breakpoints into conditional breakpoints.

-

cond(ition) breakpoint_number break-args

- cond 3 i == 3

-

Remove the condition but keep the breakpoint.

-

cond(ition) breakpoint_number

- cond 3

-

-

List Breakpoints

- i(nfo) b(reakproints)

(gdb) i b

Num Type Disp Enb Address What

1 breakpoint keep y 0x000055555555513d in slen at slen.c:2

breakpoint already hit 1 time

2 breakpoint keep y 0x0000555555555170 in main at strlen.c:6

breakpoint already hit 1 time

4 breakpoint del y 0x0000555555555157 in slen at slen.c:7

5 hw watchpoint keep y p

breakpoint already hit 3 times

(gdb)

Let’s take a closer look at the output of info breakpoints, which lists each breakpoint and its attributes.

-

Num (Identifier)

- The unique indentifier of the breakpoint, which is passed to as an argument to several GDB commands, such as

deleteandcondition.

- The unique indentifier of the breakpoint, which is passed to as an argument to several GDB commands, such as

-

Type (Type)

- The breakpoint’s type can be one of

breakpoint,watchpointorcatchpoint.

- The breakpoint’s type can be one of

-

Disp (Disposition)

-

A breakpoint’s disposition indicates what will happen to the breakpoint afterthe next time that GDB hits it. The values can be:

-

keep

- The breakpoint will be unchanged after the next time it’s reached. This is the default disposition of newly created breakpoints.

-

del

- The breakpoint will be deleted after the next time it’s reached. This disposition is assigned to any breakpoint you create with the

tbreakcommand.

- The breakpoint will be deleted after the next time it’s reached. This disposition is assigned to any breakpoint you create with the

-

dis

- The breakpoint will be disabled the next time it’s reached. This is set using the

enable oncecommand.

- The breakpoint will be disabled the next time it’s reached. This is set using the

-

-

-

Enb (Enable Status)

- The status of the breakpoint (enabled or disabled).

-

Address (Address)

- The breakpoint’s location in memory.

-

What (Location)

- The source file and line number where the breakpoint is set. Watchpoints will instead list the symbol name that is being watched (the variable is just a memory address with a name).

Clear Breakpoint

- clear

- Clears a breakpoint at the next instruction that GDB will execute. This method is useful when you want to delete the breakpoint that GDB has just reached.

- cl(ear) function

- cl(ear) line_number

- cl(ear) filename:function

- cl(ear) filename:line_number

Enable Breakpoint

- en(able) 2

- en(able)

- Enable all breakpoints.

- en(able) o(nce) 2

- Disable breakpoint after the next time it causes GDB to pause execution.

Disable Breakpoint

- dis(able) 2

- dis(able)

- Disable all breakpoints.

Delete Breakpoint

- d(elete) breakpoint_list

- d(elete) 2

- d(elete) 2 5 6

- d(elete)

- Delete all breakpoints.

Breakpoint Command Lists

Breakpoint command lists are a hidden gem of GDB. They allow you to issue a batch of commands each time a specified breakpoint is hit.

The format is the following:

commands breakpoint-number

...

commands

...

end

+ breakpoint-number

- The identifier of a current breakpoint.

+ commands

- A newline-separated list of any valid GDB commands.

Let’s see some examples. We’ll use the following simple program:

#include <stdio.h>

int fibonacci(int n) {

if (n < 2) {

return n;

}

return fibonacci(n - 1) + fibonacci(n - 2);

}

int main(void) {

printf("Fibonacci(3) is %d.\n", fibonacci(3));

return 0;

}

We’ll start by adding a breakpoint at the top of fibonacci(). We’d like to see the value of n every time, but we don’t want to edit the source file and stick a printf in there, nor do we want to print the value every time GDB hits the breakpoint in the recursion.

(gdb) b fibonacci

Breakpoint 1 at 0x1141: file fibonacci.c, line 4.

(gdb) commands 1

Type commands for breakpoint(s) 1, one per line.

End with a line saying just "end".

>printf "fibonacci was passed %d.\n", n

>end

(gdb) r

Starting program: /home/btoll/hugo/benjamintoll.com/content/post/fibonacci

Breakpoint 1, fibonacci (n=3) at fibonacci.c:4

4 if (n < 2) {

fibonacci was passed 3.

(gdb) c

Continuing.

Breakpoint 1, fibonacci (n=2) at fibonacci.c:4

4 if (n < 2) {

fibonacci was passed 2.

(gdb)

Continuing.

Breakpoint 1, fibonacci (n=1) at fibonacci.c:4

4 if (n < 2) {

fibonacci was passed 1.

(gdb)

Continuing.

Breakpoint 1, fibonacci (n=0) at fibonacci.c:4

4 if (n < 2) {

fibonacci was passed 0.

(gdb)

Continuing.

Breakpoint 1, fibonacci (n=1) at fibonacci.c:4

4 if (n < 2) {

fibonacci was passed 1.

(gdb)

Continuing.

Fibonacci(3) is 2.

[Inferior 1 (process 10502) exited normally]

(gdb)

This is great, but let’s reduce the verbosity by adding the silent command. We’re overwrite the command we just created.

(gdb) commands 1

Type commands for breakpoint(s) 1, one per line.

End with a line saying just "end".

>silent

>printf "fibonacci was passed %d.\n", n

>end

(gdb) r

Starting program: /home/btoll/hugo/benjamintoll.com/content/post/fibonacci

fibonacci was passed 3.

(gdb) c

Continuing.

fibonacci was passed 2.

(gdb)

Continuing.

fibonacci was passed 1.

(gdb)

Continuing.

fibonacci was passed 0.

(gdb)

Continuing.

fibonacci was passed 1.

(gdb)

Continuing.

Fibonacci(3) is 2.

[Inferior 1 (process 10683) exited normally]

(gdb)

We can optimize this by having GDB automatically continue until the end of the program so we don’t have to do it manually. Simply add the continue command after the body of the command definition:

(gdb) commands 1

Type commands for breakpoint(s) 1, one per line.

End with a line saying just "end".

>silent

>printf "fibonacci was passed %d.\n", n

>continue

>end

(gdb) r

Starting program: /home/btoll/hugo/benjamintoll.com/content/post/fibonacci

fibonacci was passed 3.

fibonacci was passed 2.

fibonacci was passed 1.

fibonacci was passed 0.

fibonacci was passed 1.

Fibonacci(3) is 2.

[Inferior 1 (process 10954) exited normally]

(gdb)

Watchpoints

A watchpoint isn’t assigned to a line of code, but to a variable. Since a variable is just a name for a memory address, it therefore will not have a location assigned to it, as demonstrated in the table of information produce by the info breakpoints command.

GDB will pause its execution every time the variable that is watched changes value.

Set Watchpoint

- watch var

Here’s an example of GDB pausing execution after setting a watchpoint for the variable p, which is in scope when the slen function in slen.c is pushed onto the stack. After the program is run with the value foobar and the watchpoint is set, next is issued several times, with GDB printing out p’s value at each iteration:

(gdb) r foobar

Starting program: /home/btoll/strlen/strlen foobar

Breakpoint 1, slen (s=0x7fffffffe2ca "foobar") at slen.c:2

2 char *p = s;

(gdb) watch p

Hardware watchpoint 2: p

(gdb) c

Continuing.

Hardware watchpoint 2: p

Old value = 0x0

New value = 0x7fffffffe2ca "foobar"

slen (s=0x7fffffffe2ca "foobar") at slen.c:4

4 while (*p != '\0')

(gdb) n

5 p++;

(gdb)

Hardware watchpoint 2: p

Old value = 0x7fffffffe2ca "foobar"

New value = 0x7fffffffe2cb "oobar"

slen (s=0x7fffffffe2ca "foobar") at slen.c:4

4 while (*p != '\0')

(gdb)

5 p++;

(gdb)

Hardware watchpoint 2: p

Old value = 0x7fffffffe2cb "oobar"

New value = 0x7fffffffe2cc "obar"

slen (s=0x7fffffffe2ca "foobar") at slen.c:4

4 while (*p != '\0')

(gdb)

Conditional Watchpoint

-

watch (condition)

-

watch p > 2

(gdb) r foo Starting program: /home/btoll/strlen/strlen foo Breakpoint 1, slen (s=0x7fffffffe2cd "foo") at slen.c:2 2 char *p = s; (gdb) watch p > 2 Hardware watchpoint 2: p > 2 (gdb) c Continuing. Hardware watchpoint 2: p > 2 Old value = 0 New value = 1 slen (s=0x7fffffffe2cd "foo") at slen.c:4 4 while (*p != '\0') (gdb)

Delete Watchpoint

- d(elete) watchpoint_number

Note that GDB will automatically delete the watchpoint when it goes out of scope, so manually deleting it may be unnecessary, depending.

Other GDB Commands

continue

- c(ontinue)

- Resumes execution of the program until the next breakpoint is triggered or the program terminates.

- c(ontinue) n

- Optional, tells GDB to resume execution and to ignore the next n breakpoints.

finish

-

fin(ish)

- This command will take you out of the current stack frame and pause execution at the top of the next frame. It can be very handy when you’ve stepped into a function when you intended to step over it. Simply instructing GDB to

finishwill place you back where you would’ve been had you not stepped into the function. - In the case of a recursive function,

finishwill only take you up one level of the recursion in the stack frame. To break out of the recursive stack entirely (or when wanting to break out of a loop but stay within the current stack frame), see theuntilcommand.

If there are any intervening breakpoints, GDB will pause execution.

- This command will take you out of the current stack frame and pause execution at the top of the next frame. It can be very handy when you’ve stepped into a function when you intended to step over it. Simply instructing GDB to

next

- n(ext)

- Single-steps to the next line of code. If the line of code to be executed is a function, it will execute it without pausing within it.

- n(ext) n

- Steps n lines of code (does not enter a function).

step

- s(tep)

- Single-steps to the next line of code. Unlike its brother next, it will enter a function and pause within it.

- s(tep) n

- Steps n lines of code (will enter a function).

until

- u(ntil)

- u(ntil) function

- u(ntil) line_number

- u(ntil) filename:function

- u(ntil) filename:line_number

shell

- she(ll)

- Temporarily exit to a command line.

exitto get back togdb.

- she(ll) function

- she(ll) xargs -0 printf %s\n < /proc/6074/environ

- Print the environment variables (set when the process was first created) for PID 6074.

- Doesn’t show any environment variables then added via

setenv.

call

- cal(l)

- Call a

Clibrary function.

- Call a

- cal(l) getenv(“SHELL”)

Miscellaneous

i(nfo) proc

(gdb) info proc

process 471165

cmdline = '/foo/a.out foobar'

cwd = '/foo'

exe = '/foo/a.out'

Text User Interface Mode

The last thing I’m going to cover is TUI (text user interface) mode. This is a nice view of the source file that uses the curses library.

Simply pass the -tui switch when starting GDB.

gdb -tui strlen

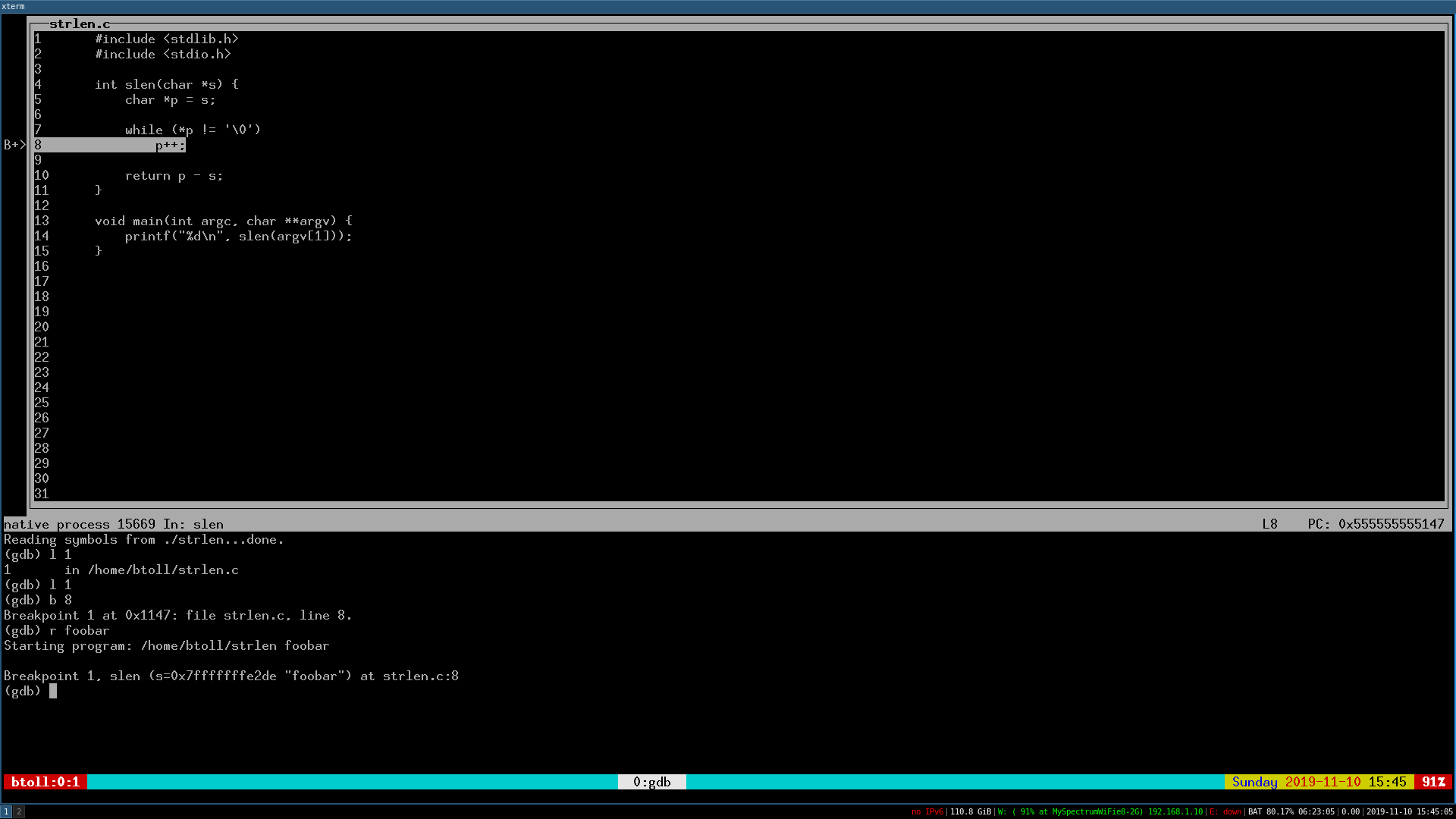

Here, you can see that I set a breakpoint on line 8 and then ran the program with an argument of “foobar”. GDB then halted execution at that line and is now waiting for further instructions.

You issue commands as you normally would in the pane below. Note that if you step through the source, the line where the breakpoint was set will be indicated by a B+ symbol on the left (at least on my system), and the currently-executing line will be demarcated by a caret (>) and visually highlighted.

Besides the obvious benefits of seeing the source code of what is being executed, you can use GDB’s list command to jump to another source file of that was compiled into the binary.

For example, let’s move the slen function into its own file:

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include "slen.c"

void main(int argc, char **argv) {

printf("%d\n", slen(argv[1]));

}

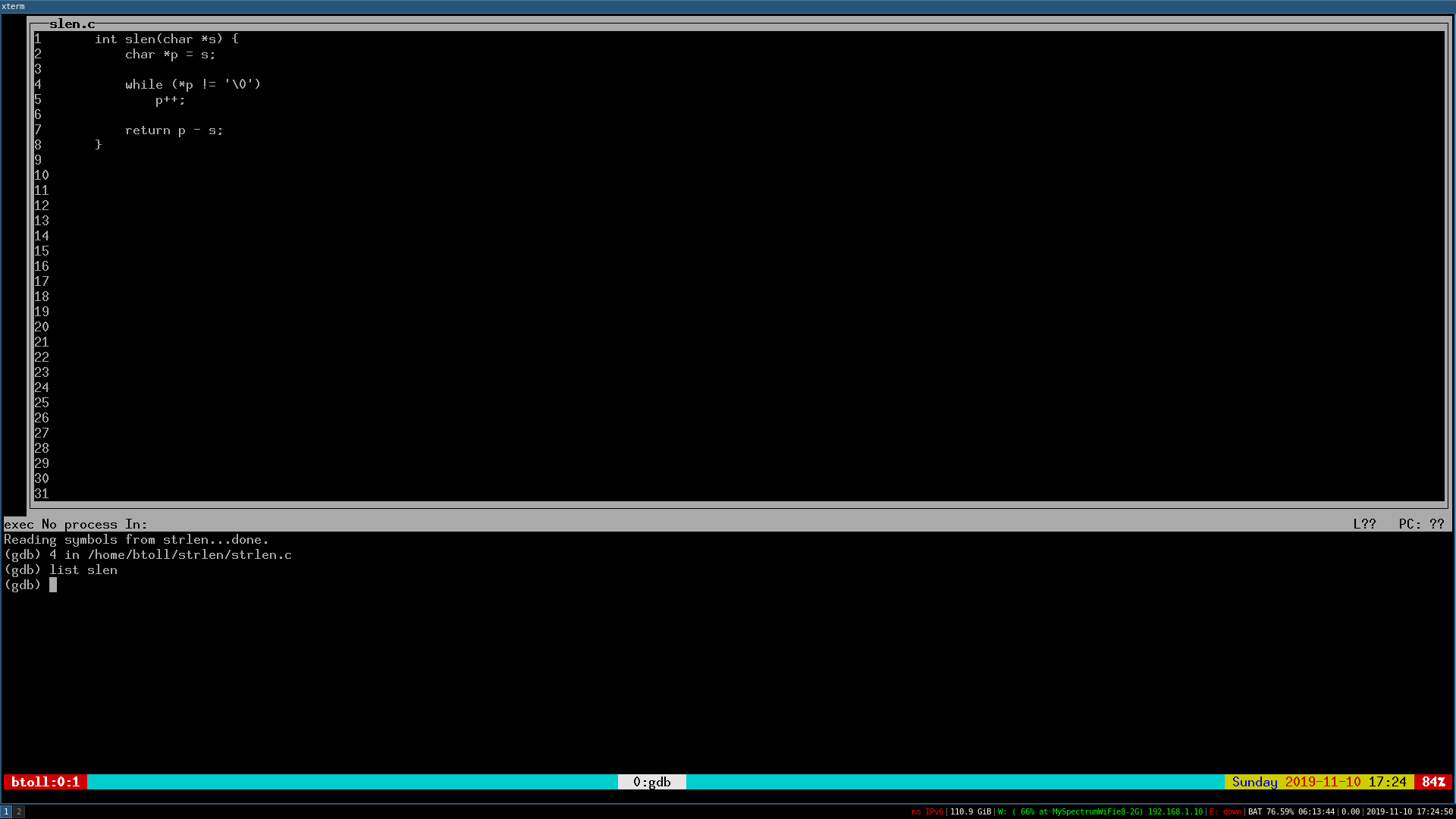

Now, here’s the result of viewing it in TUI mode after starting GDB with the -tui flag and issuing the command list slen:

You can see that GDB’s focus when loaded was in the strlen.c source file, but that when the list command was issued to jump to the other file that the header now shows that the focus is now in the slen.c source file. To get back to the previous file, simple invoke list main.

Ok, that’s pretty cool.

To scroll within the source file, use the up and down arrow keys. To scroll with command history, use CTRL-P and CTRL-N.

Lastly, if you start up GDB without issuing the -tui switch but want to see the view, you can toggle it using the command CTRL-X-A.

For those who’d like more

TUIaction, here’s a sweet tutorial.